Is she naked or nude in that painting?

Debating the line between between nakedness or nudity in art history - and how Google's SafeSearch tells us what their take is and what we should think.

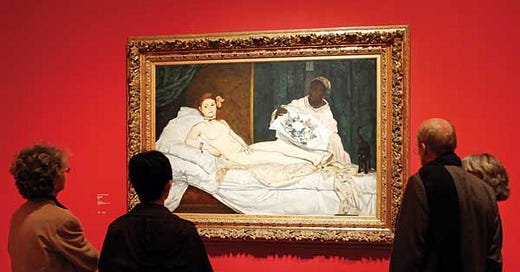

If you visit Uffizi in Florence or certain sections of one of the many museums in Paris, you’ll maybe find that there are a lot of people without clothes on. Many of which you, we, are crediting with that was just how beauty, the study of the human form, or the male form at least, and no sexual innuendo. However, it’s not the same vibe as seeing Édouard Manet's "Olympia" (1863) in Paris and Titian's "Venus of Urbino" (1538) - is it?

In the study of art history, the distinction between 'nude' and 'naked' has been a subject of extensive discourse, reflecting deeper inquiries into the representation of the human form and its cultural implications. The 'nude' in art is traditionally associated with the idealized, often depersonalized portrayal of the human body, celebrated for its aesthetic form and beauty within a specific cultural and historical context. When I studied back in University I remember reading Kenneth Clark, ‘The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form,’ 1956, and he articulates this distinction by asserting that "to be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word 'nude,' on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone." Clark's analysis underscores the nude as an art form that transcends the mere absence of clothing to embody an ideal of human beauty and proportion, often removed from the individuality and vulnerability inherent in the human condition.

Conversely, the concept of 'naked' conveys a sense of vulnerability, individuality, and the presence of the subject's personal and emotional dimensions. John Berger, in "Ways of Seeing" (1972), provides a critical perspective on this distinction, particularly in the context of the male gaze upon the female form. Berger posits, "To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself." This observation highlights the power dynamics at play in the representation of nakedness, where the subject's personal identity and autonomy are often overshadowed by the viewer's perception and the cultural coding of nudity. Which by its very nature means that it’s moving. Berger's critique invites a reevaluation of how nakedness challenges the conventions of the nude in art, emphasizing a more authentic, unidealized representation of the human body that acknowledges its reality and imperfections.

There is something to be said about that point that they both make. That to be ‘nude’ is to be seen by others, and not recognised for oneself. It seems as if it’s the subjects gaze that tells us if they’re aware of their own nudity or not - however, that’s not really true for everyone is it? Or not even the gaze or the confrontation, but a physical mannerism that tells the viewer that they’re aware that we see them. I’m sorry, but to me, that seems like a logic that is only true for one group and not others. Here’s an example of why. Imagine the Sistene Chapel or the Last Judgement by Michelangelo - were all naked women? Wouldn’t that be a different vibe? I think there’s a fair good chance that that would be blocked by Google’s SafeSearch too.

What happens today when we Google the Sistine Chapel? There’s a lot of nakedness, or nudity, and there’s suggestive mannerism in the way that we can guess that they might know they are being seen.

Hmmm. How about being even more explicit in our Google search?

That still seems completely safe. Sound. Traditional. Beauty. Nude. According to Google that is.

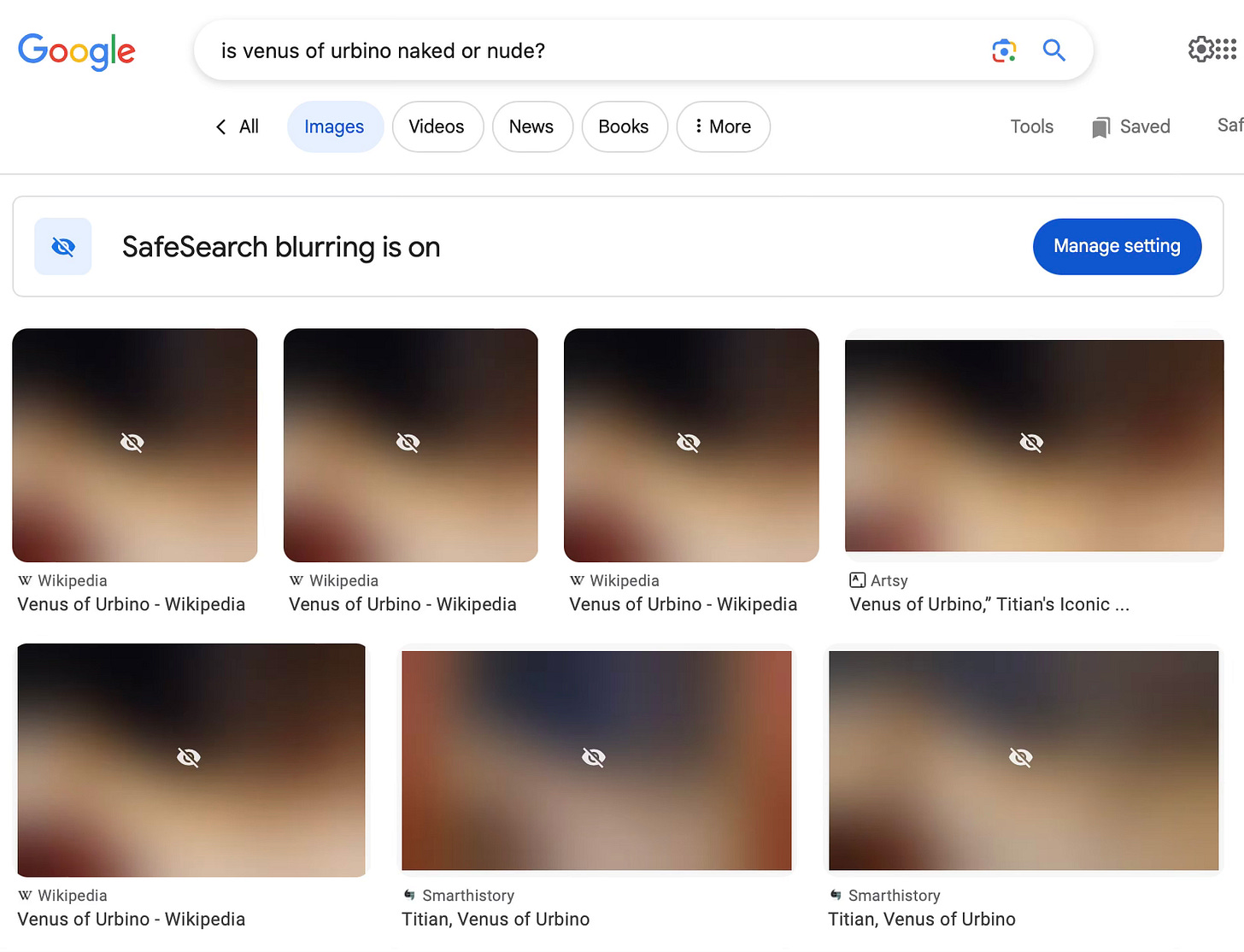

However, Google dosen’t think so about Venus.

Changing perception of the same painting

If we take Titian's "Venus of Urbino" (1538) is widely regarded as a depiction of the nude rather than the naked. This distinction, rooted in the art historical context and the interpretive frameworks provided by critics and theorists, hinges on the portrayal's intention, the subject's presentation, and the viewer's reception.

The argument that Kenneth Clark makes, and is later discussed by John Berger among others, the nude is an idealized form, often presented in a manner that abstracts the body from its individuality and vulnerability, elevating it to a symbol of beauty and aesthetic perfection. Titian's Venus embodies this idealization. She is presented in a composed, serene manner, reclining on a bed, her gaze meeting the viewer's. The setting and her pose, along with the use of soft, harmonious color, contribute to a portrayal that transcends the personal, emphasizing the aesthetic and sensual qualities of the form itself.

Clark's distinction between the naked and the nude is pertinent here; "Venus of Urbino" does not convey the discomfort or vulnerability associated with being naked. Instead, Venus is depicted in a way that celebrates the human form's beauty, making the work a quintessential example of the Renaissance nude. Her direct gaze and the intimate setting invite the viewer to appreciate the form and composition, engaging with the work on an aesthetic level that aligns with Clark's notion of the nude as an art form that "carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone."

Furthermore, John Berger's analysis in "Ways of Seeing" suggests that the nude, especially in the context of the female form viewed through the male gaze, is often constructed for the viewer's pleasure, a concept that can be applied to the "Venus of Urbino." Berger's distinction between being naked ("to be oneself") and being nude ("to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself") underscores the role of the viewer's perception in defining the subject as nude. In this case, Venus is presented in a manner that is meant to be seen and admired, her identity and individuality secondary to her role as an embodiment of ideal beauty and sensuality.

Titian's "Venus of Urbino" is considered a depiction of the nude, aligning with Renaissance ideals of beauty, the aesthetic celebration of the human form, and the art historical distinctions between the nude and the naked. It engages with themes of sensuality, beauty, and the viewer's gaze, positioning Venus within a tradition of art that elevates and idealizes the human form. However, is the next question not - did that change? How was the reception at the time, or when the artwork was travelling from museum show to museum show?

What’s interesting is also that this public analysis of ‘Venus of Urbino’ and others like this keeps changing. Google definitely thought it was more ‘naked’ than ‘nude.’

What are other examples of ‘naked’ vs ‘nude’ in art history? What do you think?

Here are other examples, including two, you’ve already seen:

Édouard Manet

Manet's approach to depicting the human body, particularly women, was revolutionary for his time and often sparked controversy. His famous painting "Olympia" (1863) is a prime example. Unlike the idealized and passive nudes typical of the period, "Olympia" confronts the viewer with a direct gaze and a sense of individual presence that suggests nakedness more than a classical nude. Manet's portrayal was seen as a stark departure from the tradition of depicting the female body as an object of male desire, instead presenting a woman with agency and self-awareness.

Lucian Freud

Lucian Freud's work is characterized by an intense, unflinching examination of the human form, often described as "naked" rather than "nude." Freud's subjects are depicted with a raw honesty that exposes their vulnerabilities and imperfections, stripping away any idealization or abstraction. His paintings, such as "Benefits Supervisor Sleeping" (1995), showcase the texture, weight, and reality of flesh, emphasizing the individuality and the lived experience of his subjects. Freud's work is a celebration of the human body in its most naked truth, devoid of any classical or aesthetic pretensions.

Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville pushes the boundaries of how the body, particularly the female body, is represented in art. Her large-scale paintings often depict flesh in extreme conditions—swollen, marked, and distorted—challenging conventional beauty standards and the traditional portrayal of women as objects of desire. Saville's subjects are naked in the most profound sense, exposed and unapologetic, forcing viewers to confront their own perceptions and biases about the body and identity. Works like "Propped" (1992) not only display the body in its naked reality but also engage with themes of gaze, identity, and the politics of representation.

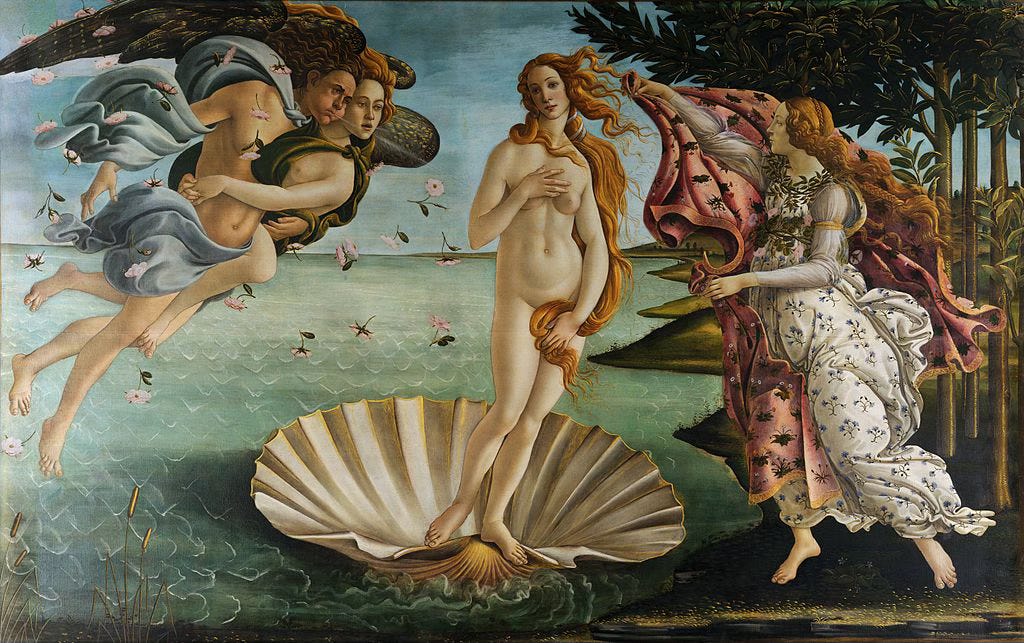

Sandro Botticelli

Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" (c. 1484-1486) is an iconic example of the nude in Renaissance art. This painting depicts Venus, the goddess of love, standing nude on a seashell as she arrives at the shore. Botticelli's Venus is an idealized figure, embodying the classical notions of beauty and harmony. Unlike the raw nakedness depicted by artists like Freud or Saville, Botticelli's nude is ethereal and transcendent, capturing the human form in its most divine and perfected state. The work reflects the Renaissance interest in classical antiquity, humanism, and the exploration of divine beauty through the human body.

Titian

Titian, a master of the Venetian school, is renowned for his sensuous approach to the nude. His painting "Venus of Urbino" (1538) is a celebrated example, showcasing a reclining nude woman who gazes directly at the viewer. This work is celebrated for its warm color palette, the soft rendering of flesh, and the intimate, yet dignified portrayal of the female form. Titian's Venus is both a subject of desire and a composed, self-possessed figure, embodying a complex interplay between viewer and subject. The painting has influenced countless artists and continues to be a benchmark for the portrayal of the nude in art.

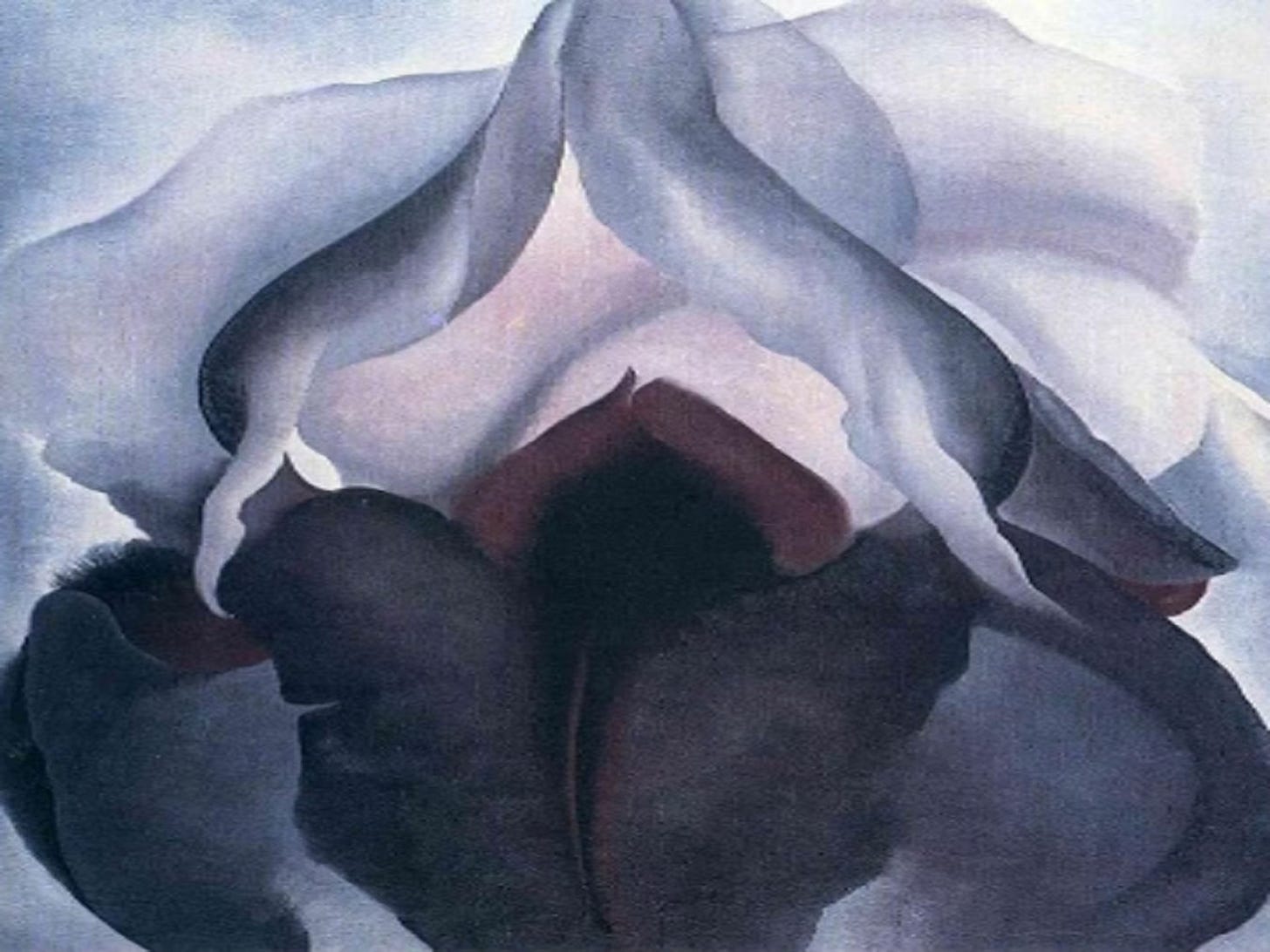

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe, though not typically known for human nudes, approached the concept of the nude through her abstracted and highly sensual depictions of flowers and landscapes, which have often been interpreted as reflections on femininity and the natural form. O'Keeffe's work, such as "Black Iris III" (1926), uses organic forms to explore themes of beauty, sexuality, and life forces in a manner that parallels the traditional nude. Her abstraction of natural forms into evocative, almost bodily shapes challenges and expands the boundaries of how the nude can be conceptualized and appreciated. O'Keeffe's art, with its bold simplicity and profound depth, invites a reevaluation of the nude, moving beyond the human figure to find nudity and sensuality in the natural world.

Okay, but what do you think?